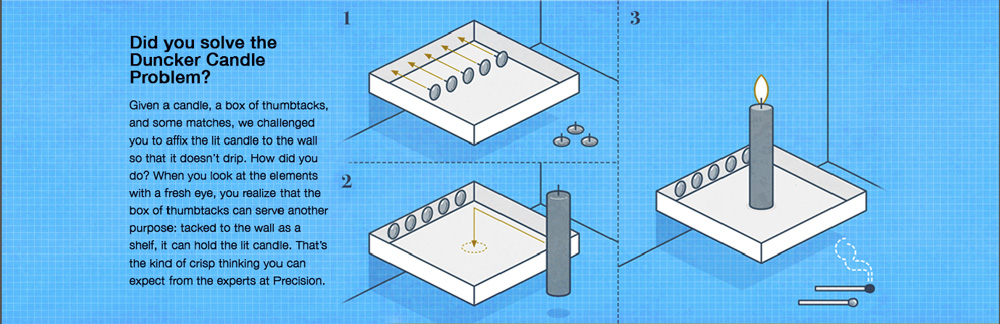

Given a candle, a box of thumbtacks, and some matches, can you affix a candle to the wall and light it so that it doesn’t drip on the floor?

Known as Duncker’s Candle Problem, this puzzle is actually a cognitive performance test, measuring the influence of functional fixedness—the cognitive bias that makes it difficult to use familiar objects in unfamiliar ways. It was devised by the Gestalt psychologist Karl Duncker as part of his thesis, presented at Clark University, then broadly published posthumously in 1945.

Most people only see the candle, the matches, and the box of thumbtacks as a whole; that’s a factor of functional fixedness. Yet, if you consider the problem more creatively, you realize that the box filled with thumbtacks can be emptied—and tacked to the wall as a shelf, it can hold the lit candle.

When Duncker originally challenged his test subjects with the problem, few solved it. Then he rearranged the elements, putting the thumbtacks in a pile outside their box. Not surprisingly, people arrived at the solution much more quickly, because they immediately perceived the box as an individual item that could be used to solve the puzzle. In this case, functional fixedness was not an issue, because a box is meant to hold things.

Duncker’s experiment shows that functional fixedness becomes a hurdle when people face new issues they have not previously seen or solved. It creates a mental block—one that can prevent even the smartest people from seeing a simple solution. It’s a built-in bias, and it can color everything. Yet, once we can recognize it, we are free to probe alternatives, consider options, and ask “Why not?”

The answer may be as surprising as it is obvious.